When the Atlantic hurricane season starts in June, it may be one of the United States’ most explosive hurricane years to date. That’s according to researchers and experts whose 2024 hurricane season predictions indicate a troubling trend: a collision between warm waters and shifting climate systems could produce near-record tropical storms—notable for their strength and sheer numbers.

2024 to See More Tropical Storms and Hurricanes

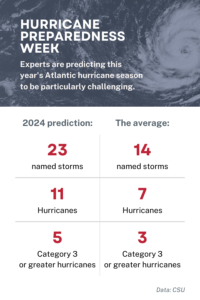

In terms of quantity, researchers with the Department of Atmospheric Science at Colorado State University predict that the 2024 Atlantic hurricane season will be far above average with 23 named storms, 115 named storm days, and 11 hurricanes. Those numbers far outpace the typical Atlantic hurricane season, which produces on average just more than 14 named storms, 69 storm days, and seven hurricanes.

Meanwhile, scientists from the University of Pennsylvania’s Mann Research Group provided 2024 hurricane season predictions featuring even bigger numbers—between 27 and 39 storms, with their estimated total at 33 storms.

By comparison, in ’23—the fourth most-named storm year since 1950—the Atlantic basin saw 20 named storms. Seven of those were hurricanes, and three intensified to major hurricanes. Hurricane Idalia was the only one to make landfall in the U.S.

More Major Category Hurricanes Expected This Year

Even more concerning than the large total number of hurricanes predicted this year is the size of those storms. This year, CSU researchers predict the Atlantic will produce as many as five Category 3, 4, or 5 hurricanes, and that the probability of a major hurricane making landfall is far above average.

According to North Atlantic Ocean historical tropical cyclone statistics from CSU, 2005 holds the record for both the most total hurricanes—15—and the most major hurricanes—seven. Included among them were Category 4 Hurricanes Dennis, Katrina, Wilma, and Rita, all of which made landfall in the U.S.

The 2020 season brought so many storms we ran through names from the Western alphabet and went to the Greek alphabet. The season started with Category 1 Hurricanes Hannah, which made landfall in Texas, and Isaias, which made landfall in North Carolina. Category 4 Hurricanes Laura and Eta made landfall in Louisiana in August and south-southwest of Puerto Cabezas, Nicaragua in November, respectively. In September, Category 2 Hurricane Sally made landfall in Alabama followed by Category 2 Hurricanes Delta and Zeta both hit Louisiana again in October.

The Making of a Storm

How we got here is a matter of science—and how colliding conditions are favorable to hurricane creation.

In order for a hurricane to form, two things must be present: warm water and a weather disturbance, such as a thunderstorm. It’s the interaction of that storm—which pulls in warm surface air from all directions—and water that is at least 80 degrees Fahrenheit, which provides fuel, that gives a hurricane its force.

According to NOAA, “hurricanes start with the evaporation of warm seawater, which pumps water into the lower atmosphere. This humid air is then dragged aloft when converging winds collide and turn upwards. At higher altitudes, water vapor starts to condense into clouds and rain, releasing heat that warms the surrounding air, causing it to rise as well. As the air far above the sea rushes upward, even more warm moist air spirals in from along the surface to replace it.

As long as the base of this weather system remains over warm water and its top is not sheared apart by high-altitude winds, it will strengthen and grow. More and more heat and water will be pumped into the air. The pressure at its core will drop further and further, sucking in wind at ever-increasing speeds. Over several hours to days, the storm will intensify, finally reaching hurricane status when the winds that swirl around it reach sustained speeds of 74 miles per hour or more.”

Warm Waters and Climate Shifts Make For Turbulent Hurricane Season

With sea surface temperatures in the eastern and central tropical Atlantic much warmer than normal this year, conditions are conducive for hurricanes. Because warmer waters mean more heat energy—or fuel—for a storm, they also make for greater risks of huge, powerful hurricanes.

The combination of those record-warm waters in much of the Atlantic Ocean, plus the transition in the tropical Pacific from El Niño conditions to La Niña conditions by the peak of hurricane season, are prompting the increase in both the number and projected severity of hurricanes this year.

During El Niño, trade winds weaken and warm water is pushed toward the West Coast. El Niño may favor stronger hurricane activity in the central and eastern Pacific basins, but it suppresses it in the Atlantic basin. During La Niña, trade winds are stronger than usual, pushing more warm water toward Asia, while off the west coast of the Americas, upwelling increases, which brings cold, nutrient-rich water to the surface. But, while La Niña suppresses hurricane activity in the central and eastern Pacific basins, it enhances it in the Atlantic basin—the United States’ hurricane zone.

Such shifts in the dynamic and thermodynamic conditions, combined with those warm ocean surface waters, are making for what is expected to be a record-breaking turbulent hurricane season. Looking ahead, these 2024 hurricane season predictions serve as a reminder of the importance of proactive planning and preparation. While predictions offer valuable guidance, it only takes one storm to wreak havoc and devastation. Coastal residents are urged to take heed of the forecast, stay informed, and take necessary precautions to safeguard lives and property. As we brace for the uncertainties of the months ahead, resilience and readiness will be paramount in the face of nature’s fury.