In 2021, typically-mild Seattle hit a record high of 108 degrees Fahrenheit. In April of 2022, India reached 121 F. A few months later, a U.K. heatwave melted a runway at London’s Heathrow Airport. The world is literally on fire. And yet, oddly and frighteningly enough, in the U.S. experts believe we may just have to fight fire with (more) fire, and manage the smoke and risks that come with it.

Government officials, fire departments, and forestry officials alike now realize that America’s long experiment with suppressing fire, a wildfire mitigation strategy that began in the late 1800’s, has been an abject failure, and one that has left a dangerous amount of fuel lying around our neighborhoods and across increasingly tinder-dry public lands.

Fire is best viewed and understood as a triangle of essential components: heat, fuel, and oxygen. Reducing one or more of those helps manage fire.

While there are no universal, failproof fire management techniques or wildfire mitigation strategies that work in every ecosystem, there exists ample evidence and hard lessons-learned about what tactics and mechanisms work to minimize destructive wildfires in a variety of conditions and settings. Like any public hazard, to say ‘it takes a village “is both trite and wholly accurate.

We’ve Moved (Fuel) to the Fire Zone

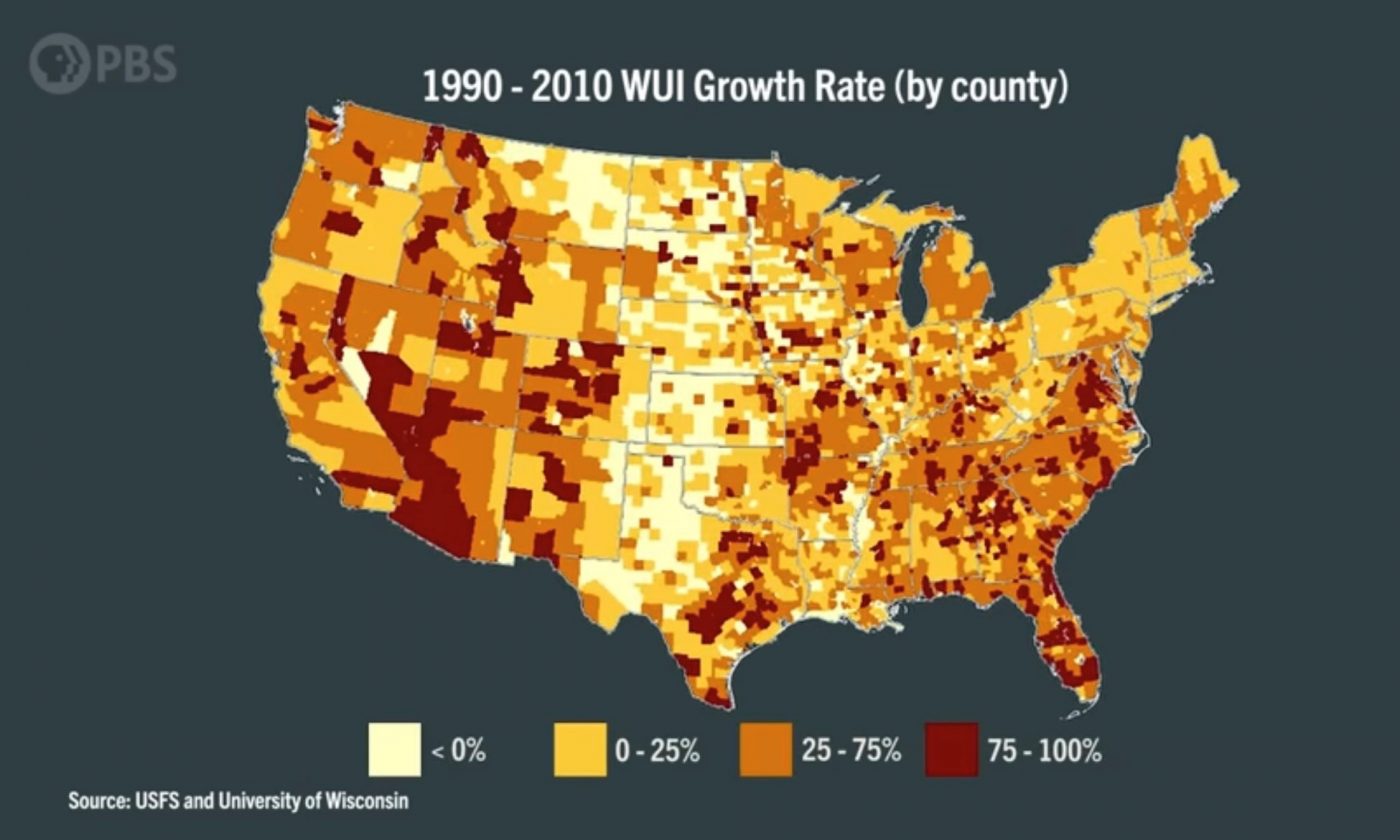

While most people associate fire damage with forests (thanks, Smokey Bear), the havoc wreaked by fire is now predominantly in areas comprising homes and people. As Americans have moved closer and closer to the area where houses and wildland vegetation intermingle—the Woodland Urban Interface, or WUI—roughly one-third of houses in the U.S. now sit in the WUI, increasing the risk that fires will reach and torch man-made structures.

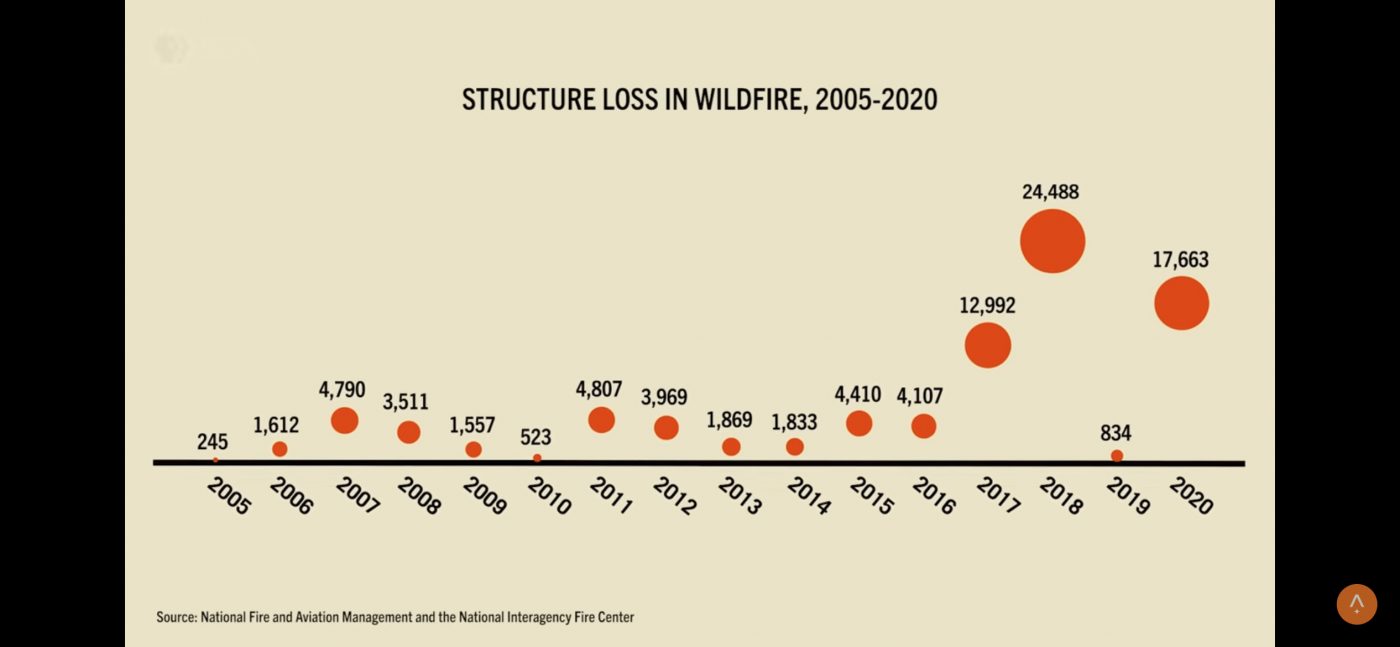

In California in 2021, for example, 80% of homes lost to fires were outside of forests. The acreage lost to wildfire in Western forests is now virtually equaled by fires in the nation’s grasslands. Nationally, the number of structures lost to fire annually from 2005 to 2020 grew 72-fold.

Because those burns leave behind felled trees and dead vegetation, we have been literally adding mountains of fuel to an already dangerous fire ecosystem, all in a time of rising temperatures and drought.

Burn, Baby…Burn?

While the idea of purposely setting a fire in a forested area might seem a crazy, dangerous health hazard to some, it’s one of the oldest proven wildfire mitigation strategies. At least 70 different uses of fire embraced by Indigenous Peoples, who regarded fire as “medicine”, have been documented across the world. In North America, Indigenous Peoples in have been conducting light burns with “good fire” for centuries.

For thousands of years, Australia’s Aboriginal people in Arnhem Land, a vast wilderness area in the northeast corner of Australia’s Northern Territory, had used prescribed fire to prevent out-of-control fire before losing the land to encroachment by white settlers. With the Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act of the 1970’s, they revived that practice. The result? Over the past two decades, the total area of fire burned in the western Arnhem Land has diminished significantly. As an added plus, a more active savanna burning regime over the last seven years has led to a reduction in greenhouse gas emissions equal to more than 7 million tons of carbon dioxide.

Back in the U.S., states and governments looking for better wildfire mitigation strategies are also taking note. In 2021, the California Legislature and Governor Newsom committed funding to “support expansion of cultural burning, and seek to better integrate tribal organizations and cultural fire practitioners into public agency prescribed fire projects and programs.”

Nonetheless, prescribed fires do occasionally escape, at a rate of 1.5% for the National Park Service, or less than 1% according to Forest Service records. Managing naturally caused fires has a similar rate of failure. When an escape occurs, however, its destruction makes headlines.

The largest recorded fire in New Mexico history was started by two escaped “prescribed burns.” The Hermit’s Peak fire near Las Vegas bolted away on April 6, 2022 when unexpectedly gusty winds blew sparks beyond control lines, merging it with the Calf Canyon Fire. Together, they scorched 341,000 acres before being fully contained.

New Mexico Governor Michelle Lujan Grisham’s reaction was to insist that federal agencies rethink spring burns. The chief of the U.S. Forest Service, Randy Moore, responded by announcing a halt on prescribed burning for a 90-day review period. In September, Moore lifted the ban, with the provision that prescribed fires would only occur on National Forest System lands if a series of recommendations had been implemented at the burn location and conditions were certified as appropriate for a controlled fire on the proposed day of the burn.

Public opposition to prescribed fires can also be significant, due to concerns about smoke and related health risks. But in determining risk, one nationwide report found that out of 23,050 prescribed fires conducted on 3.7 million acres, only 199 resulted in an escaped fire, with one minor injury reported, one insurance claim (less than $5000), and no lawsuits. The risk of injury on prescribed fires is also significantly less than many other land management activities. For example, a 2015 report found that estimated logging fatalities rates (per 100,000 workers) between 1963 and 2013 were more than 17 times greater than wildland firefighting, which is even more hazardous than prescribed burning (Weir et al. 2020) in the hierarchy of risk.

Local Fire Dept. staffing also represents a challenge for expanding prescribed burns. As Daniel Swain, a climate scientist at UCLA notes, “in the middle of winter, for example, in a lot of places there isn’t staffing to do prescribed fire on a large scale. . … when it might actually be most reasonable and safe to do some of these prescribed fires.”

Trimming and Logging as Wildfire Mitigation Strategies

Modern Forestry techniques use the thinning of forests and wooded areas to redistribute growth potential to fewer trees advancing past the sapling stage, leaving a stand with a desired structure and composition. Researchers from the Interior Columbia Basin Ecosystem Management Project found that thinning and other thinning-like stand treatments can substantially influence subsequent fire behavior at the stand level by either increasing or decreasing fire intensity and associated severity of effects.

Similarly, studies of ponderosa pine forests of the southern Blue Mountains and elsewhere revealed that thinning in the absence of prescribed fire had a moderating effect on fire behavior for a number of years.

But the combination of prescribed fire plus thinning efforts for accomplishing fuel reduction and fire management objectives demonstrates that 1+1 can equal 3.

Examination of the aftermath of the 2014 Carlton Complex Fire in north central Washington, which burned 250,000 acres and 300 homes in a single day, showed that a 12,000-acre ‘doughnut hole’ within North Central WA remained untouched by the inferno. The area survived, researchers from the Nature Conservancy and the U.S. Forest Service believe, because it had been previously thinned and burned.

Timber industry advocates will often point to their logging and harvesting efforts as a useful source of fire management, but research conducted in the Sierra Nevada mountain range in the late 1990’s suggests otherwise. In fact, researchers from the University of California, Davis, concluded: “Timber harvest, through its effects on forest structure, local microclimate, and fuel accumulation, has increased fire severity more than any other recent human activity.”

The felling of large, old growth trees and their canopy was found to have also disrupted the web of connectivity among key players in the healthy forest ecosystem.

In the case of the Sierra Nevadas, which UC Davis teams studied over five years, research revealed a codependent, symbiotic web of fungi, flying squirrels and the trees’ root system. Researchers observed that flying squirrels—which reside in the canopies of old growth trees—subsist largely on the truffles produced by healthy underground fungi called mycorrhizae. Trees rely on—and share—these critical mycorrhizal fungi to gather the nutrients and water they need. These fungi spores pass undigested thru the squirrels’ digestive tract, dispersing the fungi throughout the forest.

In addition, researchers concluded that the “cutting of smaller, ‘understory’ trees, followed with controlled burns”, was the most effective method for maintaining forest health. Reducing competition for critical soil moisture among the remaining, older trees helped them ward off pests and disease.

Timber industry advocates have also argued that post-fire logging has a net positive effect on future forest health, but that theory was thoroughly debunked by research following the Biscuit Fire in Oregon in 2002.

Since the majority of fires and destruction originates in non-forest areas, what wildfire mitigation strategies can homeowners and community leaders adopt to minimize damage?

Education, Assessment, and Smokey Bear

Perhaps the most effective community approach available to preventing fire damage is a combination of public education, home assessment, and mitigation activities.

I first learned about home assessments while volunteering for Team Rubicon’s wildfire mitigation efforts in Colorado. In such, mitigation programs trained volunteers go door to door in communities to help educate and encourage homeowners to harden their homes and grounds—the defensible space of their property—to minimize the effects of any future fires. Home assessment efforts take a comprehensive, 360-degree view of potential risks to homes, yards, and accompanying structures, recognizing that fire embers can travel a mile or more, penetrate small openings (screens) and cause large scale damage.

In that operation, under the leadership of Incident Commander Duane Poslusny, Team Rubicon volunteers, known as Greyshirts, conducted 117 home assessments for risks. Then, they provided mitigation efforts, including tree cutting, shrub/fuel removal and risk reduction recommendations such as replacing screens, windows or substituting rocks for shrubs in proximity to wooden structures, for 108 residents.

A 2015 study in New Mexico found that two-thirds of homes lacked key elements of defensible space, but 20% of the average home hazard could be reduced by undertaking simple mitigation steps.

More Education, More Codes

In the 1990’s Edmonds, WA, began a home visit program where they hired senior women to go door-to-door to inspect homes for fire safety. As a result of advertising and awareness raised, not just from the visits themselves, fires went down by an amazing two-thirds during the program. According to Phil Schaenman, of research firm TriData, “When funding was cut for this program, the fires went right back up. It was as perfect a social engineering experiment as you could have. Apply prevention stimulus, fires down. Take away prevention stimulus, fires go up.”

Fortified building codes are another effective wildfire mitigation strategy and means of minimizing fire damage. A stark example of this involves the 2018 Camp Fire in Paradise, CA, the deadliest in California history.

In 2008, the California Legislature adopted Chapter 7A into the California Building Code. Chapter 7A establishes minimum standards to protect life and property for a building located in a WUI Fire Area by increasing its ability to resist the intrusion of flames or burning embers.

Overall, most—86%—of the single-family homes in Paradise were built before 1990, and homes of this age fared poorly in the Camp Fire, with only 11.6% surviving the Camp Fire. The Survival rate for homes built after 2008 and adoption of new building materials and codes was 43%—nearly four times more effective.

If these tactics and developments teach us anything, it’s that a cohesive and sustained effort among industry, government and individuals is a prerequisite for humans to weather and survive fires that are increasing in ferocity, reach and frequency,

It truly does take an entire village, Smokey.

To conduct your own home assessment, consider CalFire’s Ready for Fire and the University of Nevada’s Living With Fire guides. Apartment dwellers can find useful tips from FEMA here.