Tornadoes are among the most terrifying natural disasters a community can face. Composed of a column of air rotating up to 300 mph and traveling across the landscape at speeds up to 70 mph along unpredictable paths, tornadoes strike seemingly at random. They flip cars and trucks, rip trees out of the ground, tear buildings apart, and turn loose debris into deadly projectiles.

Tornadoes form when warm, humid air rises while cool air falls inside a thundercloud, and then meets cool, spinning air at the ground. When violently rotating columns of air extend from a thunderstorm and don’t touch the ground, they’re called funnel clouds. When they do touch the ground, they become tornadoes.

No community is large enough to be safe from a tornado—as horribly demonstrated by the 2019 tornado that struck Havana, Cuba, population 2.13 million, and killed eight; the 2020 tornado that hit Nashville, population 692,587, and killed five; and the April 2024 tornado that devastated Guangzhou, China, a modern metropolis of more than 15 million people, damaging 140 buildings and killing five.

Tornadoes Around the World

Although considered a peculiarly American phenomenon, and one that has largely been concentrated along the Great Plains, tornadoes have been reported on every continent except Antarctica. While the United States has the most documented tornadic activity out of any country on Earth, that may be because the country is best at detecting and counting them—much of which has only been done in the last 30 years. Prior to the mid-1990s, when an effective tornado detection system was built, if nobody saw a tornado then it wasn’t reported and does not appear on weather records, making it difficult to accurately describe long-term and global trends. However, America’s tornado detection systems rely on Doppler radar analysis which can only indicate weather conditions in which a tornado is likely to form, on-the-ground confirmation of damage after the fact or eyewitnesses of a tornado touching down is still necessary to verify whether a tornado really did occur.

This issue of documenting tornadoes persists in rural areas in America and throughout the world, leaving tornado records incomplete and conclusions tentative. It is possible that there are tornadoes in Antarctica, it’s just that nobody has ever seen and reported one because basically nobody lives there.

The single deadliest tornado event ever recorded was on April 26, 1989, when a massive twister of speeds up to 260 mph struck central Bangladesh. Dragging over 10 miles, the tornado wiped two towns off the map, killed around 1,300 people, injured 12,000, and relegated another 80,000 homeless. Bangladesh has suffered several high-fatality tornado events over the decades, including five separate storms that each left more than 500 dead.

Bangladesh, Japan, the Philippines, India, and China comprise Asia’s own tornado alley, of sorts: It’s here that the most tornadoes are reported and the majority of deaths, damage, and injuries occur—so far as can be told. In all honesty, how many tornadoes actually happen every year is currently unknown; like most countries, none of these have America’s robust tornado detection network.

South America also has a tornado alley of its own, largely confined to the grasslands of Argentina and portions of Uruguay, Paraguay, and Brazil. While technically the second-most active tornado zone in the world—averaging about 1,000 twisters a year—its tornadoes do not produce equivalent damage and are likewise probably undercounted. In fact, the entire Southern Hemisphere reports a fraction of the tornado activity and associated damage as in the Northern Hemisphere. Australia and Africa combined account for just more than 100 tornadoes annually, and they rarely result in mass casualties or community-wide damages.

Europe experiences around one-fourth as many tornadoes as the U.S., most of which are too small to cause damage but do kill an average of a dozen people every year. In fact, the first reported tornado of 2024 actually happened in Europe, when dozens of homes were damaged and destroyed along a 4-kilometer stretch of Belgium on January 3.

In the U.S., Tornado Alley Moves East

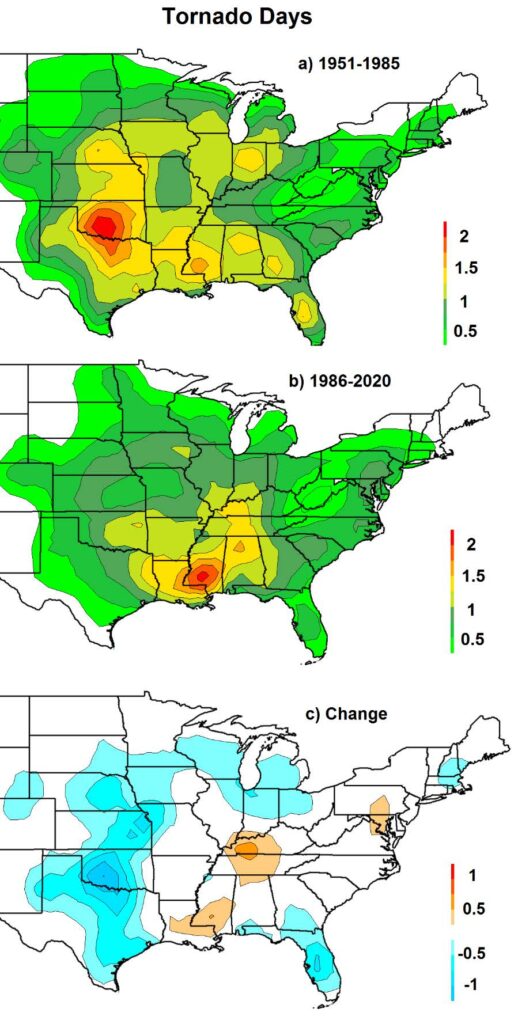

Research, along with often heartbreaking global news reports, demonstrate conclusively that tornadoes are not unique to America. In fact, the long association of twisters with America’s Great Plains states isn’t completely relevant anymore as Tornado Alley—a nonscientific definition encompassing several states—has been shifting eastward for years.

Traditionally, Tornado Alley is considered as running roughly north from Texas through Oklahoma, Kansas, and Nebraska to South Dakota, and often including neighboring states to the east and west.

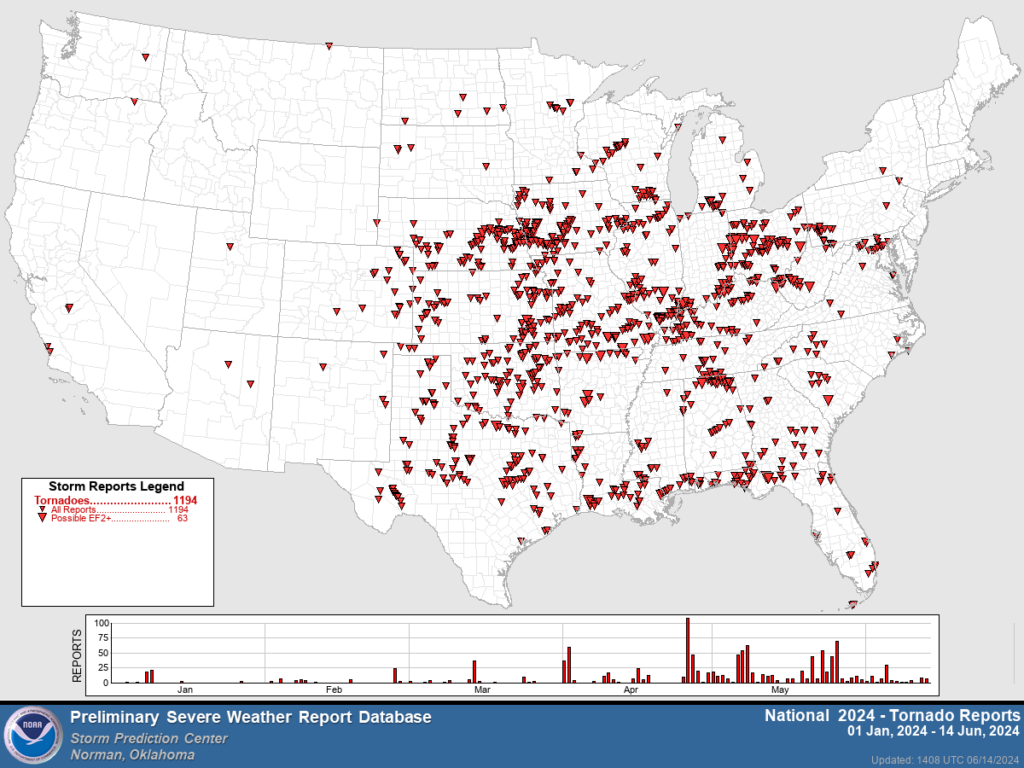

Of the 1,194 tornadoes that have already struck American soil this year, as of June 14, 2024, just more than half have been in Tornado Alley. States far outside of Tornado Alley have already experienced more tornadoes in 2024 than even most states within the Alley typically do. Take, for example, Ohio: Located hundreds of miles from Tornado Alley, Ohio has already recorded 71 tornadoes this year. The storm-prone center of Tornado Alley, Oklahoma, averages 69 per year.

Tornado Alley in the U.S. is shifting: According to a report published in the April 2024 issue of the Journal of Applied Meteorology and Climatology, since 1951 tornado activity has been shifting away from the Great Plains and toward the Midwestern and Southeast U.S. Scientists aren’t entirely sure of the reasons for the shift, however, tornadoes are more likely to form when local weather conditions are unstable and, as one tornado expert at Environment and Climate Change Canada explained to Scientific American: “warming increases instability.”

And the world has been warming.

As Tornado Alley Shifts, Damages Accrue in the South

While the Alley may be shifting, historically, fully half of the deadliest tornadoes in America have happened outside of Tornado Alley—mostly in the South—according to the Storm Prediction Center.

That’s likely due to the fact that Southern states have more trees to be toppled and thrown around, while also being both more populated and dotted with less affluent communities than the Great Plains states. The region, according to research in the science journal Nature, “already represents a maximum in the occurrence of casualties associated with tornadoes.” The research warns that the east- and southward movement of Tornado Alley further increases the likelihood of tornado-related damage and casualties.

The heightened risk of death and damage in the South underscores how exposure to disaster is as often as dependent on economic strength and community preparedness as it is on the weather.

There is a “high degree of social vulnerability in the South,” explained the director of the Atmospheric Sciences Program at the University of Georgia to Yale Climate Connections, “[The South] encapsulates a population comprised of significant Black, Hispanic, elderly, and impoverished communities…such communities have the greatest sensitivity to extreme weather events and less capacity to bounce back from them.” It is not just greater exposure to tornadoes that makes some places suffer more from their impacts than do others but also a lack of resources to prepare for and recover from disasters.

“Tornadoes do not discriminate. Severe weather, including tornadoes, can impact every state, leaving a trail of destruction in its wake,” said Jeff Byard, Vice President of Operations for Team Rubicon. “The South is no stranger to the impacts that tornadoes create. Vulnerable communities often experience additional difficulties on their road to recovery. Those are the areas where you will find Team Rubicon, making a difference in the face of adversity.”

A Banner Year Already on the Records

Even if Tornado Alley had remained static, tornadoes are more widespread than most people realize. And potentially more widespread than ever as 2024 is shaping up to be a historic year for tornadoes in America.

“This year has already seen over 1,000 tornado reports, the most active tornado season since 2017,” explained Team Rubicon Operations Manager Lia Wainwright.

The 1,118 tornado reports that had been cataloged through May 31 by the Storm Prediction Center were already a significant contrast to historical averages of 606 tornadoes in the U.S. between January and May.

And, as of June 14, there have been well over 100 tornadoes so far in the South, including 90 just between Florida and Alabama. More than 100 tornadoes have touched down in Iowa, 67 in Illinois, and 27 in Wisconsin. Even California has had five tornadoes this year.

Forecasting service AccuWeather is predicting 1,250 to 1,375 tornadoes across the United States in 2024, above the annual historical average of 1,225 but also below the 1,423 twisters reported in 2023. According to researchers from the National Severe Storm Laboratory at NOAA, the average number of tornadoes per year is essentially unchanged, however, tornado outbreaks are increasing.

In other words, while there are fewer tornado days—days in which a tornado strikes—when they do strike, they do so en masse and increasingly outside the expected places.

Climate Changes, Disasters Remain

Even as exact forecasts for tornadoes remain elusive, the toll they can be expected to have on communities as Tornado Alley U.S.A. careens east is not so vague.

“Economic losses associated with tornadoes will continue to increase in future years,” reported Nature. As communities in the South continue to grow and their neighborhoods expand, the physical and financial costs of natural disasters will keep rising—potentially three times as high because many communities in the region are already unfortunately high on the CDC’s social vulnerability index (SVI).

From Alabama to Bangladesh, tornadoes—like all disasters—most affect the most vulnerable. Adequate infrastructure, established community emergency plans, and economic vitality are critical factors for communities to maintain long-term resiliency against, and provide effective short-term responses to, disasters. That is why Team Rubicon’s response and resilience efforts center on communities lacking such elements, using the SVI to determine where to focus disaster preparation and response efforts.

“Our guiding light as we decide where Team Rubicon should respond to is taking into consideration a community’s resources and ability to respond to their own challenges,” said Wainwright. “In the words of the founder and first chief of the U.S. Forest Service, Gifford Pinochet, we must do ‘the greatest good of the greatest number in the long run’.”