In order to better appreciate the contributions of Black Americans, Team Rubicon is using Black History Month to learn and share the stories of Black trailblazers in our line of work: Emergency management and disaster response.

Today we recognize Jabbar Gibson, who during Hurricane Katrina, took the wellbeing of the community into his own hands and single-handedly evacuated more than 70 people to safety.

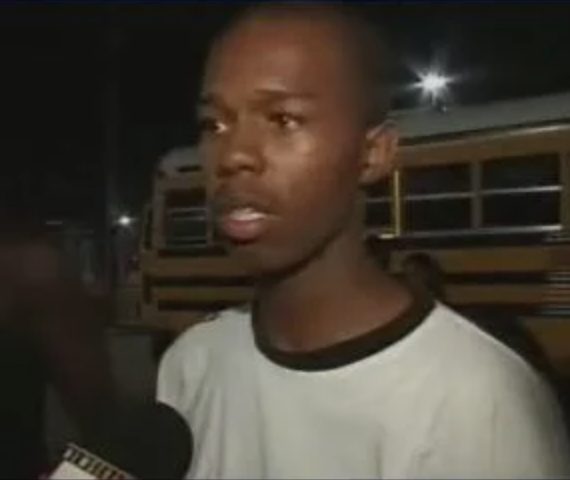

Two days after the levees broke in New Orleans in August 2005, the Houston Astrodome was opened to take in the victims of Hurricane Katrina. When the first busload of evacuees from the flooded city arrived, authorities were surprised to see 20-year-old Jabbar Gibson sitting behind the wheel.

Gibson was a young Black man who lived in the Fischer Projects that formerly stood in New Orleans’ Algiers neighborhood. Like most residents of the Fischer, he had not followed the mayor’s order to evacuate the city before Hurricane Katrina made landfall. Many of those who lived there were unwilling to abandon the building that they had called home for multiple generations. As well, very few people who lived at the Fischer owned vehicles to evacuate in, even if they had wanted to.

Dilapidated before the storm ever arrived, the Fischer sustained serious damage from Hurricane Katrina. Fallen trees had gouged large chunks from housing units. The winds shattered windows, destroyed wooden fences, lifted tile from the roof, and even ripped pieces out of the building’s brickwork. For two days Gibson, along with his friends and family, lived amongst the wreckage without power, food, or the assurance that anybody was coming to help them.

When word spread that other neighborhoods—the Ninth Ward, Bywater, Mid-City—were being swallowed by floodwaters, Gibson and a small group of Fischer residents began thinking of ways to escape. “We were desperate,” said Kerry Lavinette, a longtime resident of Fischer. “It was either that or we were going to drown.”

Gibson and some friends went out to look for help and came across a barn with a dozen abandoned school busses parked inside. They found keys to the busses in an unlocked office and after half an hour got one of the busses to start. Like many residents of the Fischer, Gibson did not own a car and never received his driver’s license, much less the certification to drive a bus. “I learned right then and there,” says Gibson, “I was driving alright for the first time.”

Now with the means for escape, Gibson and his friends returned to the Fischer and began loading people onto the bus. That’s when the police arrived.

They made everyone get off the bus and demanded that Gibson hand over the keys. Nonetheless, Gibson’s mother, Bernice, managed to convince the officers that giving Jabbar the keys and letting him take control of the bus was necessary to evacuate people who were in dire need of help. Seeing the severity of the situation, and unable to provide any assistance themselves, the police returned the keys to Jabbar and told him to get out of the city.

With some 60 people piled into the bus, Gibson set out on what would be a grueling 13-hour drive. As they left the flooded city, they witnessed traumatic scenes of floating bodies and whole neighborhoods that had seemingly been left for dead.

Even with little space to spare on the bus, Gibson stopped several times along Highway 90 and picked up people stranded by the side of the road. “I just couldn’t leave them behind,” he said. Many of the passengers were in emotional and mental distress from the previous days. Others were sick or disabled and in need of medical attention. At least a couple were pregnant.

When they reached Lake Charles, Gibson and the passengers pooled their money to refuel the bus. An attendant at the gas station gave them two full ice chests, two cases of water, and one piece of invaluable information. He told Gibson that the Astrodome in Houston was being opened as a shelter for Hurricane Katrina evacuees. Whereas before they had just been fleeing New Orleans, Gibson and his passengers now had a destination.

The drive from New Orleans to Houston typically takes five-and-a-half hours, but due to the chaos of the evacuation, Gibson was behind the wheel for roughly 13 hours. All on board breathed a sigh of relief when the bus finally reached the Houston Astrodome at 10:30 PM; however, they were not yet home free. Officials at the site initially refused them entry because they were not on one of the busses scheduled to arrive. “They were not worried about us,” says Makivia Horton, a passenger on the bus who was five months pregnant at the time.

Eventually, after 20 minutes of confusion and outrage, officials announced that Gibson and the others would be allowed into the Astrodome. Soon they would be joined there by roughly 25,000 other evacuees from New Orleans.

Gibson, like many survivors of Hurricane Katrina, would struggle personally in the years to come, but to all aboard the bus at that moment on September 5, 2005, he was a hero. “He saved my whole family’s life, and he saved everyone in the Fischer. And the world should know it,” says his mother, Bernice.

Gibson’s story illustrates how our country’s disaster response and emergency management systems have historically failed communities of color; yet his story is not one of helplessness. Instead, Gibson defined his life and legacy by the help he gave to others. While Team Rubicon does not necessarily condone the commandeering of busses, we recognize that disasters call for dramatic, out-of-the-box thinking and decisive action. We too refuse to stand by as the flood waters rise and strive to follow Gibson’s example of uncompromising compassion for neighbors in need.