I’ve responded to more than my fair share of natural disasters over the years—tornados, floods, wildfires, and hurricanes. And while I know that it’s impossible to compare one crisis to another, I sensed early on that my deployment with Team Rubicon for Hurricane Michael was truly going to be unlike any other.

It had been a while since I’d last deployed with the veteran-led disaster organization. Work and life had gotten in the way. In that time, TR had grown by leaps and bounds and I wasn’t fully sure what my role would be. Would I still fit in?

Plus, like the rest of the world, I had watched in awe as the storm’s 155 mph sustained winds and deadly surge pummeled the Florida Panhandle, Oct. 10. It was heartbreaking to see images of communities like Mexico Beach, shredded to pieces by what is currently considered the third strongest (by pressure) and fourth strongest (by wind speed) landfalling storm in the United States.

Yet when I received my deployment orders, I learned that I wouldn’t be headed there or Panama City, No, I’d be going to Marianna, a small town nearly 60 miles inland. Pulling it up on the map, it’s much closer to the borders of Alabama and Georgia than it is to the coast. I was a bit surprised, but I also trusted that TR’s local volunteers and recon team knew where we were most needed—and sometimes, that’s in the place where the cameras aren’t.

Like the early days of any disaster, getting there wasn’t without its challenges. Flight delays out of New York caused me to miss multiple connections. And while Panama City’s airport was back up and operating, it was still unable to bring flights in at night. After an unplanned overnight stay in Atlanta, I finally arrived on Oct. 16.

At the airport, I met nearly a dozen other TR volunteers, aka “Greyshirts” for the T-shirts we wear to identify ourselves in the field. They had come from as far as Hawaii and Alaska to be a part of Operation Amberjack. To my relief, It didn’t take long for this group of strangers to become fast friends.

For some, it was their first operation. Yet even the “old salts” could be heard commenting on the sights we saw during the two-hour drive to Marianna. There were miles of snapped trees and downed power lines—miles of damaged homes. At one point, we were on a major road that had been barely cleared. A good gust of wind could bring down what trees were left precariously standing. It was eerie during daylight—I couldn’t imagine it in the dead of night.

Eventually, we reached Marianna and made our way to Chipola College where our FOB (forward operating base) was located. The drive through town was surreal. Homes were destroyed; businesses blown apart. It was almost as if the small city, of less than 10,000 residents, had been bombed. Thankfully, we had a secure place to stay. Yet like the rest of the region, there was no electricity and temperatures hovered near 90 degrees with brutal humidity.

We had missed the opportunity to go out with the first strike teams. Yet after securing our cots and stowing our bags in a dark gym (always pack a flashlight!), we helped build out the FOB for the arrival of more Greyshirts.

That night, we heard the stories of the day’s work from those who had arrived before us. One team had spent the day mucking out a special needs’ daycare. They were tired and dirty, but enthusiastic. Each exuded a sense of purpose and identity that is hard to explain. Over the next few days, we too would feel the same—and I couldn’t feel more at home.

I spent my first day in the field doing damage assessments, which meant going out to meet with residents to determine what help could be provided. It was a new experience for me, learning how to enter work orders into Palantir, a mobile software system that helps Team Rubicon digitally analyze and manage community needs. The information entered would help strike teams know what equipment to bring, such as saws, skid steers, muck-out kits or tarps.

Damage assessment also affords an opportunity to listen to the stories of the survivors and give them a sense of hope. Over and over, we heard how overwhelmed they were, unsure of where to go and what to do next. Understandable when you consider that Florida’s Jackson County is among the state’s most impoverished areas, with 22.6 percent of its residents living below the poverty line, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. In Marianna, that number is 35.1 percent.

Sadly, many of the residents I met with had been preyed upon by contractors, looking to exploit their fears by charging ridiculous fees for tree removal. I can’t tell you how good it felt to see their smiles, or even get a hug when telling them our work was at no cost, and that they could tell the crooks to pound sand. Among those we helped was an 82-year-old disabled veteran whose electricity can’t be restored until several trees are cleared, making it possible for utility crews to access the property.

I went out the next day with the sawyer strike teams. As sawyers turned big trees into little ones, “swampers” (as we were called) moved the debris into piles that the skid steer could then push to the curb. Even wearing gloves and other PPE (personal protective equipment), it was dirty work that left scrapes and minor cuts. Thankfully, unlike many of my teammates, I managed to escape being stung by the bees and hornets we encountered—all riled up, as they too had lost their homes to Hurricane Michael.

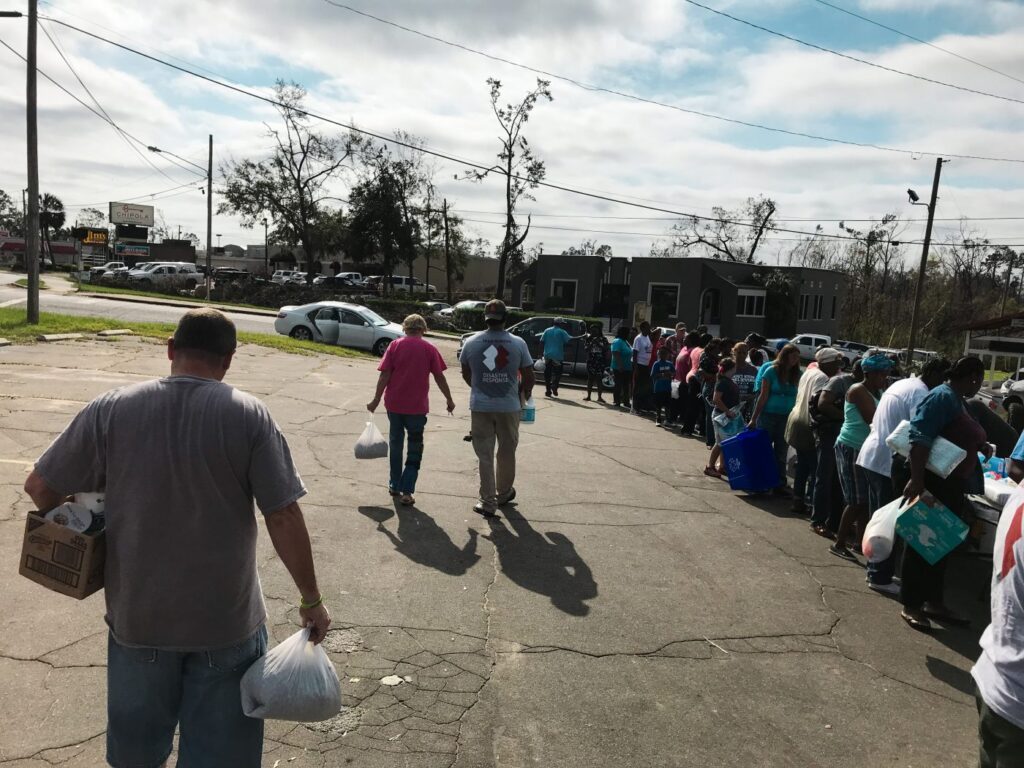

My arms are still sore from it, but one of my favorite tasks came courtesy of a Marine veteran originally from Marianna, now living in Texas, who was friends with one of our Greyshirts. He secured a tractor-trailer filled with relief supplies from El Paso. Not only did we help offload the trailer, but we helped community members carry their much-needed water and nonperishable food to their cars. We also made sure to let them know how they could reach us for assistance.

And they will need the help of Team Rubicon and other organizations for some time to come. As I write this, more than 75 percent of Jackson County is still without power. There are a lot of roofs that need to be repaired, and Florida isn’t the driest of places. It will take months, if not years, for some communities to rebound.

Of course, every individual deployment must come to an end. It wasn’t easy for me to leave knowing that so much work needs to be done. I pensively stared out the window as my wave’s van departed for the airport. Across the parking lot, I could see that those remaining were formed up for their morning briefing.

In that moment, I took comfort in the fact that there’s an army of volunteers inbound to Florida—all ready to step into the arena.