In order to better appreciate the contributions of Black Americans, Team Rubicon is using Black History Month to learn and share the stories of Black trailblazers in our line of work: Emergency management and disaster response.

Our third profile tells the story of the men and women who led the fight to integrate the field of civil service for the current generation of firefighters and first responders. Today, we recognize Black firefighters throughout America’s history as well as their powerful contribution to the field of firefighting as a whole.

The First Black Firefighters

The earliest documents identifying government sanctioned Black firefighters in the U.S. come from New Orleans in the year 1817.

Following a devastating fire that year, city authorities instated Fire Commissioners who were appointed to take charge at any fire and conscript all able-bodied bystanders to put it out. Often times, the people conscripted to help put out fires included both free and enslaved members of the Black community, a fire fighting force that was roughly 37% of New Orleans’s total population at that point in history.

A painter’s rendition of the New Orleans fire.

Up north, one of the first Black firefighters known by name (and the first woman firefighter) in U.S. history is Molly Williams. Williams was an enslaved Black woman who lived in New York city during the early decades of the 19th century and worked alongside the men of the Oceanus Volunteer Fire Company No. 1. She earned acclaim for her service during the blizzard of 1818 when she helped pull the “pumper” to the scene of a fire through deep snow. By her at-the-time male counterparts, Williams was said to be “as good a fire laddie as many of the boys.”

First Black Fire Chief

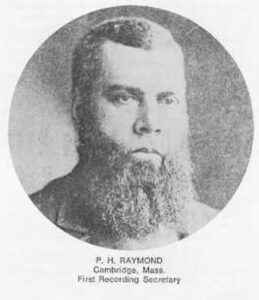

Patrick H. Raymond served as Chief Engineer of the Cambridge, Massachusetts Fire Department from 1871 to 1879, making him the first known Black Fire Chief in the U.S.. Born in 1831, Raymond was the son of man who had escaped slavery in Virginia by following Harriet Tubman’s Underground Railroad. He then went onward to become a leading and outspoken abolitionist.

During the Civil War, he and his brother both served in the U.S. Navy by taking advantage of their lighter skin tone to pass as white. At the time, restrictions kept Black men from being permitted to enlist in the Navy.

Patrick H. Raymond, the first Black fire chief.

As Fire Chief, Raymond commanded the Cambridge Fire Department when it responded to the Great Fire of Boston in 1872.

He was also one of the first U.S. Fire Chiefs to advocate for stronger fire prevention codes, an increase in the number of fire companies and company strength, and a fully-paid, permanent fire department. In a document from 1873, Raymond wrote, “the extinguishment of the fire has now become a business and has ceased to be a pastime, and greater facilities for making the business a successful one should be unhesitatingly provided.”

Invention of the Fireman’s Pole

One of the most iconic traditions in firefighting, that of the fireman’s pole, has its roots in the history of Black firefighters.

In 1878 the Company 21 Fire Station was established as the first Black fire company in the Chicago Fire Department under the command of the white Captain David Kenyon. Kenyon, who is credited with the invention of the fire pole, got the idea after seeing Black firefighter George Reid react to an alarm by sliding from the third floor to the first floor using a pole that had been temporarily lashed in place to hoist hay bales for the company’s horses.

At the time, all firehouses were equipped with spiral staircases between floors, but Kenyon was so impressed by Reid’s quick reaction to the alarm that he had a pole permanently installed. After being the target of many jokes, people realized Company 21 was usually the first company to arrive when called, especially at night, and the Chief of Department ordered the poles to be installed in all Chicago fire stations.

In 1880 the Boston Fire Department installed a brass pole, the type still used today. Within a decade, poles stood in firehouses across the nation, and later in Canada, Britain, and beyond.

Dekalb Walcott, former chief of Chicago’s 23rd Battalion, says that in Kenyon’s day, there was a competitiveness between firehouses to arrive first at a blaze—and a particular need for newly formed Black firehouses to prove themselves. “There was an ‘esprit de corps’ that came from beating other companies to a fire,” says Walcott.

The Fight for Equality

After WWII, many Black Americans returned from serving in the military overseas determined to make a place for themselves in the field of civil service.

They were met with hostility.

Jim Crow-like conditions existed in firehouses across the country and Black firefighters in newly integrated companies were subject to cruelty and violence at the hands of their colleagues.

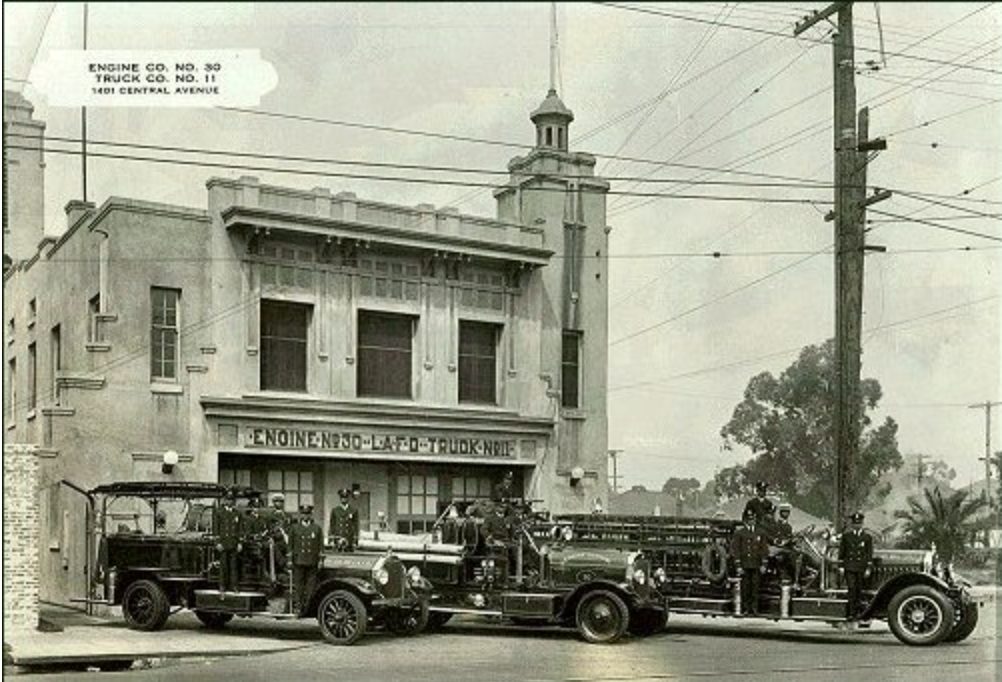

Engine Company No. 30, the first Black fire station in Los Angeles.

In opposition to the racial injustices they faced, Black firefighters began to form fraternal organizations to advocate for themselves. The most well known of these are the Vulcan Society formed in New York City in 1940 and the Stentorians established in L.A. in 1954.

A major milestone was reached in 1966 when Robert Lowery was named the 21st Fire Commissioner of the Fire Department of New York. This was the first time that a Black man had commanded a major metropolitan fire department.

In 1970, the International Association of Black Professional Firefighters was formed with the mission of increasing recruitment of Black youth in the fire service. This organization focused on the building of relationships between fire departments and the Black communities they served, and how to improve interracial relations and practices within fire departments.

Today, the International Association of Black Professional Firefighters represents more than 8,000 fire service personnel with 180 active chapters throughout the United States, Canada, and the Caribbean. Pressure applied by the IABPFF in the 70’s was instrumental in cities adopting polices that mandated fire departments better represent the demographics of the populations they served through their hiring practices.

The First Black Woman Fire Chief

Rosemary Cloud made history in April 2002 when she was named Fire Chief for the Atlanta suburb of East Point. Cloud had served in the Atlanta Fire Department for 22 years previous to assuming the role and held the position until 2015. At the height of her tenure in East Point, Cloud managed five fire stations and some 130 employees. She won numerous awards and appointments to prestigious groups like the White House National Security Council. “What we do is we go into a chaotic situation and we provide order, calm and a resolution,” Cloud told The Atlanta Journal-Constitution at the time of her hiring. “I love it.”

Rosemary Cloud, the first Black woman fire chief.

The experience of Black firefighters runs parallel to the fight for equal treatment for people of color in America. The efforts of these Black pioneers in the field of disaster response represents a legitimate push from disenfranchised men and women who desired to assume a basic civic function – to defend their homes and families. The legacy of Black firefighters demonstrates how individuals can lead the way in creating substantive change by serving.

Team Rubicon is indebted to these men and women for the impact they made in the field of civil service and strives create a community where all can be empowered to serve.